Agile development works and works well!

However, there’s a problem: At the highest level, the Agile team’s promise is: Let the stories trickle in and we will deliver! But, because of the fluid nature of “requirements”, there is no deliverable defined up front. In the absence of a concrete objective, the success of an Agile effort becomes difficult to access. Therefore, this approach does not sit too well with the project sponsors, and understandably so! They want to know, in no uncertain terms, what they are paying for! “Define the deliverable, then we’ll pay!”

So, while there is immense value in not doing a BDUF, build incrementally, put the results in front of the stakeholders and solicit feedback, the Agile process has to sit within a larger framework that defines milestones and releases.

In this post, I will attempt to describe how I recently addressed this mismatch and how we can estimate a project in an Agile landscape.

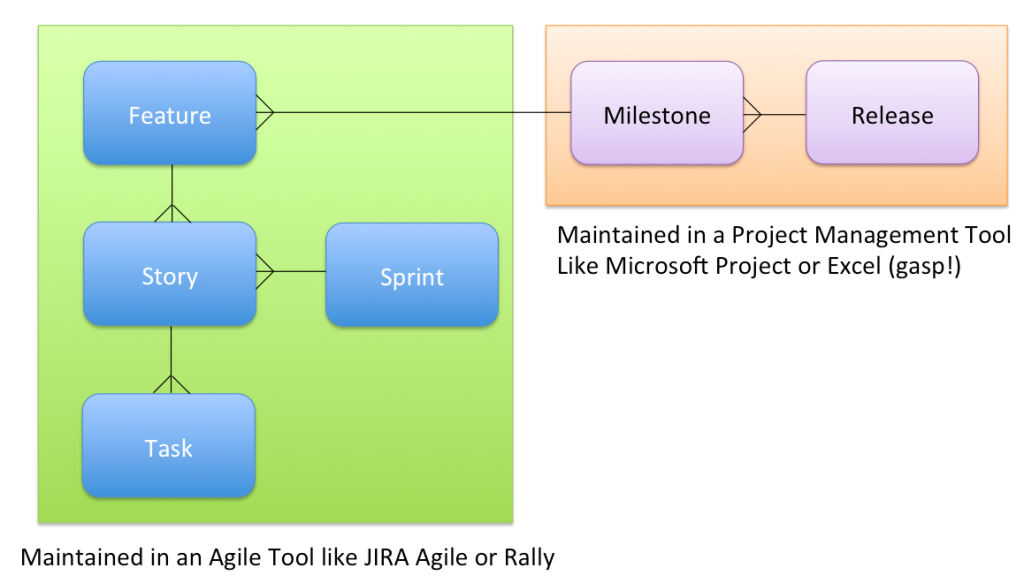

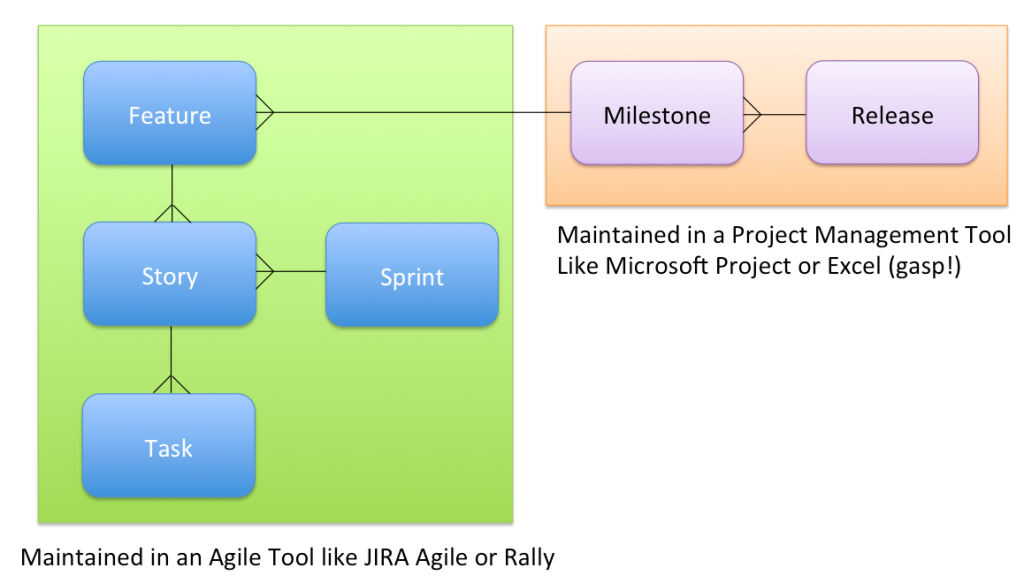

First, we need to describe the various entities that exist in this space:

As we can see, the green box encloses all the stuff that is near and dear to any Agilista: Features are made up

of one or more stories. Several Stories are developed in a Sprint. Also, Stories follow the

INVEST principle and typically span the full tech stack.

Stories are further divided into Tasks that are carried out by one or more developers and do not have to span the stack.

Ok, that was the easy part. The part where traditional project management kicks in is in the beige box.

Releases comprise one or more Milestones. And Milestones comprise of one or more Features.

The impedance mismatch is seen where we try to marry the Feature Set to a Release.

In the constantly changing world of Agile, it is entirely possible that all features are not known at the time the Release is defined.

Or, at least, it is a constantly evolving feature set. Remember, no BDUF! So how can we predict the success of a release when we don’t even know the effort that should go into a release? How do we address this mismatch? How can we make the bean counters happy and yet let development be agile?

Here is how I addressed this on a recent project.

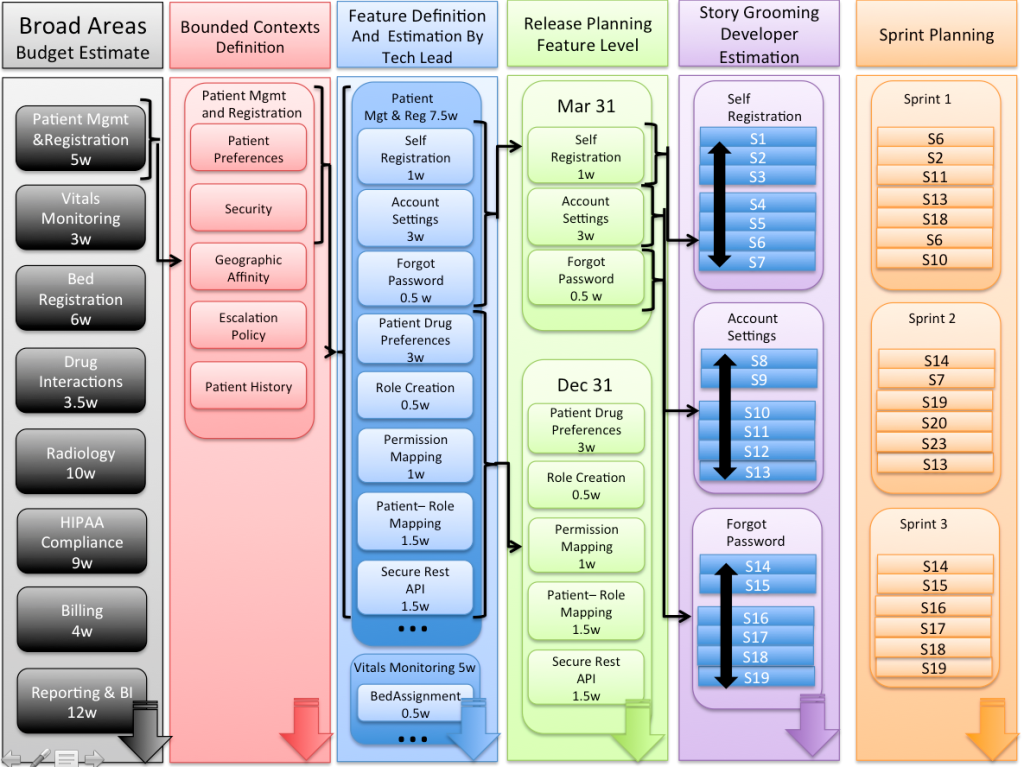

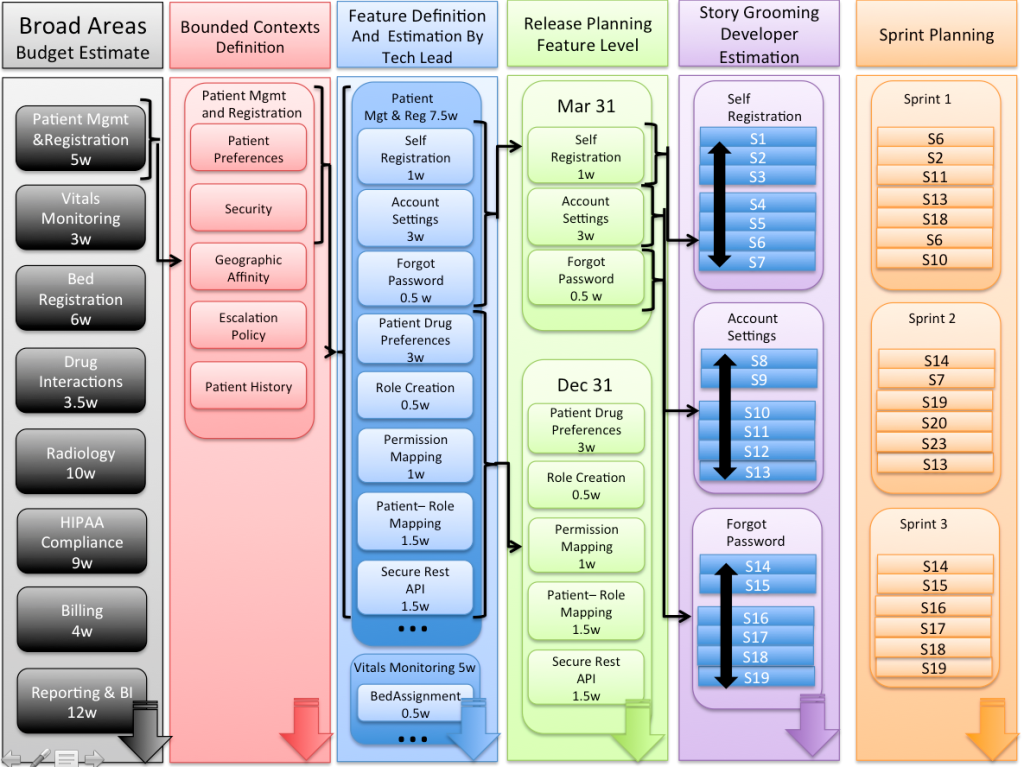

First… a picture that speaks the proverbial 1K words:

Let’s assume a fictitious Hospital Information System. We will start with the grey column on the left that defines the broad areas that are the high-level modules that such a system can conceivably have. Then we will work our way rightward, from the strategic first 4 columns to the more tactical purple and orange Story and Sprint ones.

Budget Estimate

To define a budget for the project, it will make sense to record the effort involved in each of the broad areas of the project. This is shown in the left-most (grey) column. The numbers that we come up for this effort could be from past experience or from peer teams working on similar functionality. In other words it’s a swag or a very high level estimate. This estimate can be used to predict the project cost and time.

Because the very purpose of this step is to give an idea of the whole project, it is necessary to take a swag at all the broad areas in all at once. This is unlike the other steps that are estimated incrementally as we will see.

So this estimate will keep the sponsor happy… but not for long!

Bounded Contexts Definition

This, in my opinion is the key ingredient in Agile estimation. Bounded Contexts are a term defined by proponents of

Domain Driven Design, and it is something that I’ve come to believe is a very effective way to deliver on the Agile promise.

Here we have to determine what would comprise a bounded context, then engage subject matter experts to discuss the entities that would need to be in that bounded context and keep the discussion contained.

An example will consolidate the idea:

In the Hospital Information System example, we can certainly see that a Patient is very central to every part of the system. Therefore, if we were to start discussing the Patient entity and it’s relationships, without a pre-defined boundary, the discussion could very easily bleed (no pun intended :) ) into the following areas:

- Patient Doctor interaction - What doctors does this patient usually use?

- Patient Geographic Affinity - Where the patient lives (climate, food, flora, fauna, bugs)?

- Patient Escalation - How, problems with this patient need to be escalated?

- Patient Security - How to ensure that the patient can see his own data and no one else’s?

If we do not define these bounded contexts up front, there is every chance that the discussion will lose focus and every entity that touches the Patient entity will be brought into the discussion. So we have to pick and choose ONE of the above as a potential bounded context so that we can only design that aspect. When, later, we have some time, more importantly, the subject matter experts have the time, we can discuss other bounded contexts. In true agile fashion, we build our solution bounded-context by bounded-context.

Therefore we see (in the figure above) that we have defined five bounded contexts only for Patient Management and Registration and not for Vitals Monitoring, Bed Registration etc. Those will be added when development is already underway on the first bounded context.

Of the five bounded contexts identified, let’s pick the first: Patient Security. In the discussions that surround this context the following should emerge:

- The entities that are pertinent for this context: PATIENT, ROLE, PERMISSION.

- The relationship between these entities: PATIENT has zero or more ROLEs and each ROLE has may have one or more PERMISSIONs.

- Basic UI interactions in terms of screen mockups.

Feature Definition and Estimation by Tech Leads

This is the next step that uses the output of the context meetings (outlined above for the Patient Security context). Now that we know the entities, their relationships and some broad UI screens, we can start defining features that can be delivered for this bounded context.

In the figure we see that for the Patient Preferences and Security Contexts, we can define features like Self-Registration, Change Account Settings etc..

During Feature definition we should keep in mind that features are delivered with Releases. So the feature name should define something that is complete in itself. “Patient Management” is probably too broad a name because it will likely be ongoing even after a Release is cut. But something like “Self-Registration” is something that probably wont be worked on across releases. Once a user can self-register, there’s not much else you can do under that heading.

However…

The question always comes… what if you want to improve the self-registration process? What if you wanted to add a “Login with Facebook” as an option to self-registration in a subsequent release. Then would we want to resurrect the “Self-Registration” feature. Probably not. This is because features are defined within a milestone/release and show up in the release notes. So most likely the name you will need to give to the “Login with Facebook” feature is “Oauth Support” (or “Third Party Login” if you are not too technical) and add “Login with Facebook” as a story.

Features that are defined at this stage are estimated based on experience of a senior developer/architect who is familiar with the tech stack. This estimate is expected to be more accurate than the swag that was taken in the budgeting swim lane (grey). Therefore it can potentially be less or more than the budget estimate.

Release Planning at Feature Level

Now that we have feature level estimates, and we know resources available to us, it is possible to define a release.

In the picture we see two releases defined, one named Mar 31 and another named Dec 31. The Mar 31 release comprises 3 features carried over from the blue column. (In a real life situation, one would definitely expect to see many more features per release).

This is the stage you would probably involve Marketing and ensure that the features being released are in line with the product road map and other marketing collateral.

This step sets priorities and allows us to determine what stories to start writing first. On the flip side, the features that make it in the next release will decide what bounded contexts should be defined. So this step serves as a bridge over to the tactical side of the fence.

Story Grooming and Developer Estimation

This step looks at the features that are required to be released (from the green swim lane). Those features are then broken down into stories following the INVEST principle.

These stories are placed in the prioritized backlog and moved up or down to facilitate incremental development. As the current sprint winds down, developers should start grooming these stories for the subsequent sprint.

The grooming process should be carried over a few days (at least) so that developers are given a chance to collaborate with the story author. Once groomed, the developers are expected to estimate the stories in either story points or time effort.

Groomed stories are prioritized in the prioritized backlog.

Sprint Planning

Once the stories are prioritized and estimated, depending on the velocity of the previous sprints, and the capacity available, an appropriate number of stories are moved to the subsequent sprint.

Progress Tracking

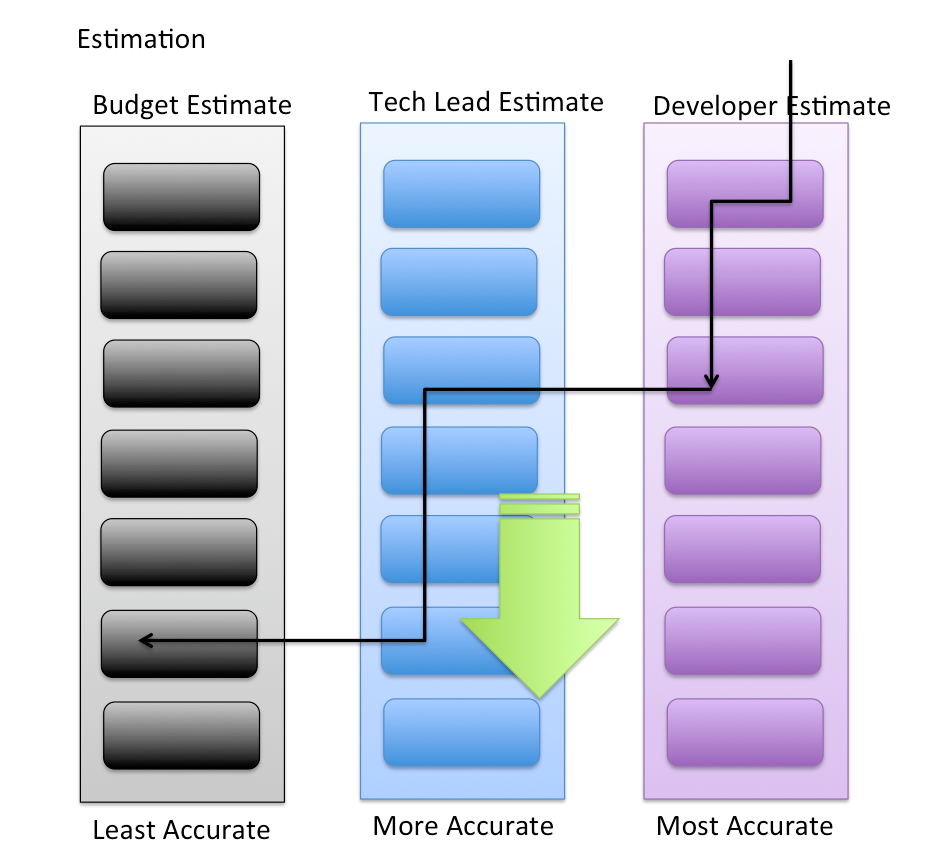

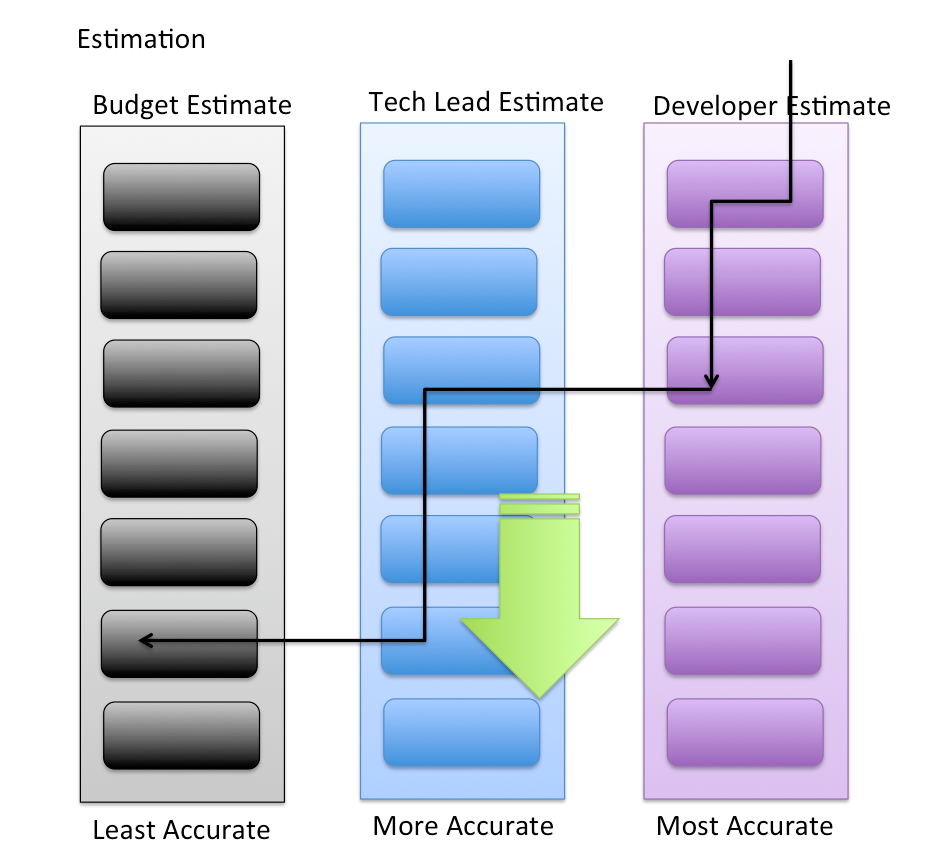

We have seen how we can estimate work at three levels:

- Estimates by peer group when the budget is defined. This is a high level estimate for purposes of budgeting

- Estimates by the tech lead/architect when features are defined. This is for the purpose of release planning.

- Estimates by developers when stories are defined. This is for the purpose of sprint planning.

These estimates need to be recorded in a project management tool (like Microsoft Project).

Looking at the picture above, we can see that the developer estimate is the most accurate; then comes the tech lead estimate and finally the budget estimate that was made in the beginning of the project.

The developer estimates are not too far in the future; they are estimated when the stories are groomed and therefore not available for bounded contexts and features that are not yet defined.

The next best estimates are those that are given by the tech lead when the bounded contexts are broken into features. This occurrence precedes story grooming and therefore is available over a longer period of time.

The estimates to fall back on in the absence of other estimates are always the budget estimates.

In the picture, we see that the arrows keep moving downwards and therefore over time, as bounded contexts are defined and stories are groomed, estimates will keep improving.

The only thing that is left to do is to pull these estimates into Microsoft Project. In the event you are using JIRA Agile, there is this plugin that will do this for you. All that is left to do is to define milestones and releases and group features against them. Remember, all you have to pull into Microsoft Project are the Features, not the stories.

In Microsoft Project, you can create a baseline at a point where you are comfortable with the position of the black arrow. From that point onward, you can track against that baseline.

What is not mentioned

Building an application bounded-context by bounded-context does cause churn, of that, there is no denying. One key enabler for such incremental development would be the existence a robust testing policy and of course, Continuous Integration. But I’ll save that for another post.

Conclusion

We first identified the artifacts that can be tracked using the Agile process. Then we defined a process to plan a release and a sprint. Finally we defined a process to estimate the effort over time and measure that progress against a base line.

Now the agilistas are happy and so are the bean counters! Stake holders can see incremental results, developers don’t have to deal with stale requirements and peace and joy reigns all around!